Cinema and social reality. End of the first part of the “When Stories Meet” short film programme

Cinema tells real and created stories, cinema realises the idea of the creative person to say something, cinema communicates the values that emerge from society, from the experience of the social. Cinema is able to combine and highlight not only the issues, values and life of today’s society, but also the experiences of history. Cinema can show the past and the vision of the future in the present.

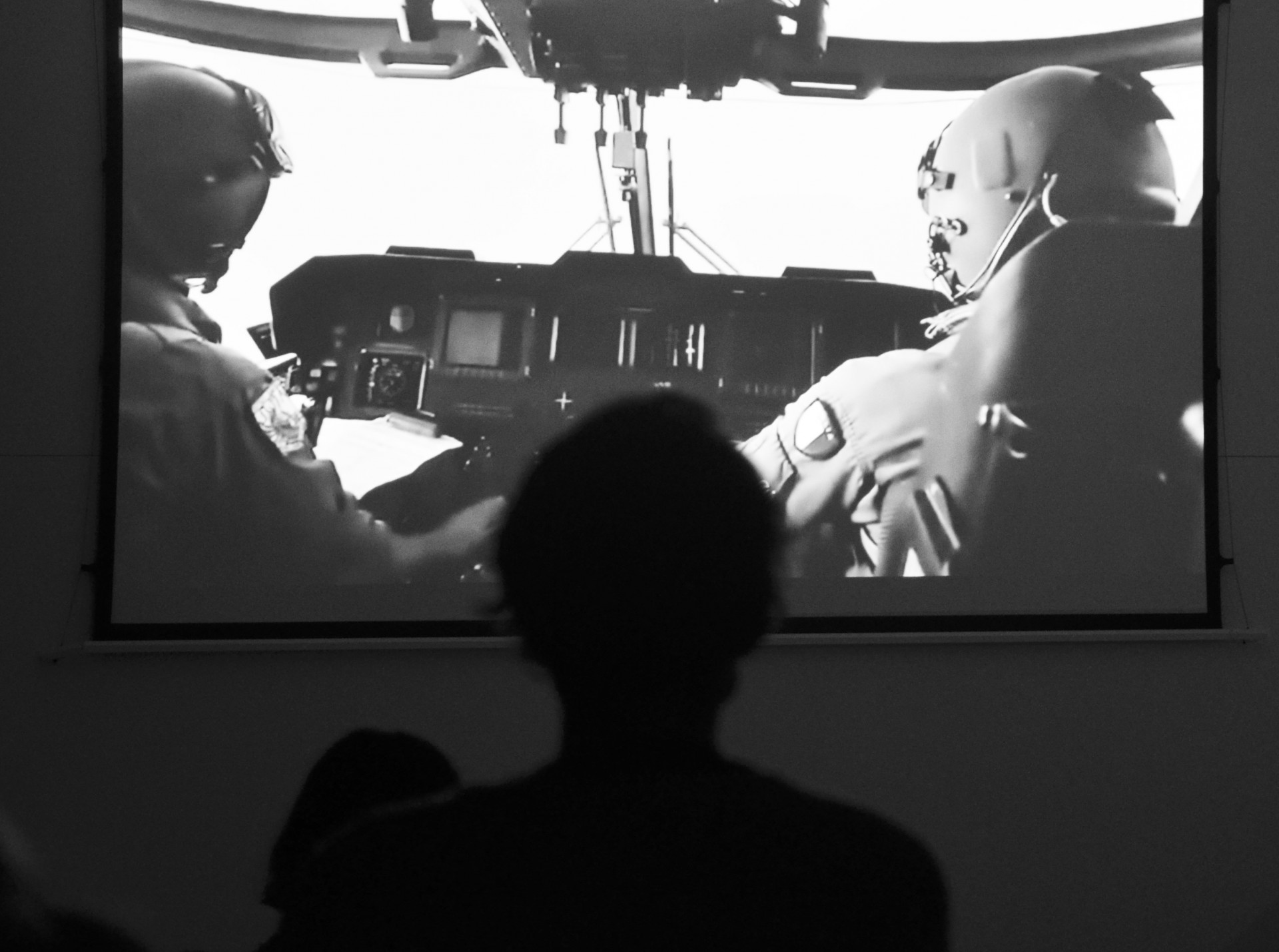

Screening footage / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

Screening footage / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

By combining the advantages of colour cinematography and sound effects, cinema has the potential to be the most effective mass-media tool for capturing the attention of audiences. But does this attraction only serve to expand the entertainment industry, leaving the viewer hungry for new experiences as they become immersed in the stories of the protagonists, emotionally involved in the action sequences, and broadening their moral judgements as they become familiar with new normalized social situations?

Moral values communicated through the medium of cinema have a lasting impact on the viewer. Therefore, cinema can easily become a means of instruction and education for the masses. The colors, sounds, contrasts, contexts, and personalities of the characters in a film can highlight, make sense of, or diminish certain parts of the reality depicted. The fact that cinema influences a person’s moral compass does not necessarily mean that this influence is positive. On the one hand, cinema reveals and helps to understand phenomena such as the relationship between parents and children, people’s everyday trials and tribulations, and on the other hand, it can normalize or even heroize processes that have a negative impact on people’s lives, such as violence, harmful habits, and the culture of crime.

Shots from the discussion / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

Shots from the discussion / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

The question of whether cinema only tells us about social reality, or does it also create it? In a public discussion at the National Martynas Mažvydas Library on the 25th of January, film producer Viktorija Cook, migration sociologist Giedrė Blažytė, host of the documentary storytelling podcast Martyna Šulskutė, and Farah Mohammed, a Syrian who has been working in Lithuania as an educator for five years. The discussion was moderated by Aušra Raulušonytė, Development Communication Coordinator. The discussion was part of the Vilnius Short Film Festival’s special programme “When Stories Meet”, curated by “Artscape” and “Vilnius Cinema Shorts”.

Shots from the discussion / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

Shots from the discussion / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

Films do tell stories in one way or another – stories about characters, stories about ideas and values, stories about the world of the creative artist. When we talk about films that reveal something new about social problems and tell stories about people facing them, the question arises as to how much they need to portray reality. Martyna Šulskutė, representing the responsible journalism platform NARA, shared her thoughts that while in both cinema and journalism, storytelling comes from a “resistance to reality”, in cinema, it is not necessary to visualise reality exactly as it is. In journalism, the aim is to tell the story of a particular person as realistically as possible. But in cinema, the story of one person is often the story of many people. Dramaturgical elements are used to highlight that commonality; objectivity is not a priority here.

Shots from the discussion / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

Shots from the discussion / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

But objectivity is an essential characteristic of scientific research. They also tell a story. But here, the assumptions, methods and results should not depend on the value judgements, personal interests or perspectives of the storyteller. Giedrė Blažytė, sociologist and research manager at “Diversity Development Group”, presented the results of the 2021 study on the attitudes of the Lithuanian population towards ethnic and religious groups. Refugees were the group singled out in the study. The social distance of the Lithuanian population towards refugees seems to have increased significantly after the exponential increase in migration numbers at the Lithuanian-Belarusian border in the summer of 2021. 47-48% of the respondents indicated that they would not be willing to live in a neighborhood with a refugee or would not be willing to rent them a house, compared to 27% in 2020. Giedrė Blažytė says that this figure is not very surprising, as ⅔ of the respondents said that they had never met a refugee in reality. The opinions of these respondents were, to their credit, shaped by the information they found in the public domain and the media, and the voices of politicians were mainly heard in the media.

Shots from the discussion / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

Shots from the discussion / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

Understanding that the narratives and discourses about migrants and refugees that are created, reproduced and re-created in the media have an impact on the formation of people’s opinions on the subject, it is even more curious to ask what impact cinema has or can have on the formation of those opinions. Opinions about the reality that surrounds people lead to established norms about how to evaluate the phenomena that are happening around us in society. These norms and “unwritten” agreements create social reality. Victoria Cook, a member of the creative team of Oleg (2019), which won two Silver Crane statuettes and two prizes at the National Film Awards of Lithuania, and producer of “Inscript”, has launched a project to allow screenings of Oleg in prisons under the authority of the Department of Prison Services, as an educational tool. In the discussion, Victoria Cook argued that while films work very well as analytical material, she would not want writers or directors to make films with the intention of changing attitudes. And whether the attitudes are changed to be negative, or positive, such a film would be somewhat like propaganda. The producer added that a film never tells its own story – well, unless it’s an autobiographical film – the story is told through the interpretation of the filmmaker, the input of the creative team at different stages of the film’s development, the sounds that are highlighted, the colors that are manipulated, the contexts that are used to awaken the viewer’s emotions.

Discussion moderator Aušra Raulušonytė / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

Discussion moderator Aušra Raulušonytė / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

And yet, without real stories, people, situations and a willingness to share memories and experiences, a film that allows us to get closer to real “migrant lives” would not be in the cinema. Cinema can change social reality by allowing the viewer to see sides of reality that are not revealed by the daily news media or by politicians. That side of reality is the human story, the reasons for (un)choices, the feelings experienced, the achievements and disappointments. Farah Mohammed, who currently works as an educator at “Artscape” Arts Agency alongside her other creative activities, came to Lithuania as a refugee five years ago. Farah Mohammed shares her experience that refugees and people from other vulnerable groups seem to have an obligation to share their stories – they are automatically expected to. “Telling a personal story is neither a privilege nor an exploitation in itself,” shared Farah Mohammed. She said that sometimes one wants to tell one’s story and sometimes one does not; sometimes it is easy to tell one’s story and sometimes it is difficult; sometimes one tells one’s story as a storyteller and sometimes one relives it. The educator said that the more prepared the listener is, the more he knows the context of the events, the more open and freer from preconceived pictures he is, the truer and more vivid the story he is able to tell.

Shots from the film screening / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

Shots from the film screening / Photo by Algimantas Černiauskas

The live discussion was followed by a screening of 5 short films, which invited the participants to immerse themselves in migrant lives, to travel to a multicultural world and to take a critical look at their own inner beliefs, stereotypes and the elements of everyday life that shape our social reality. The 5 films screened at the event – BABA, The Last Journey to the Sea, Labas, salaam, Silence and Migrating Image – are available for screening at LRT Media Centre until 12 February.

Photo of Algimantas Černiauskas

Photo of Algimantas Černiauskas

This event closed the first part of the special programme “When Stories Meet”. From February to May, “Artscape” and short film agency “Vilniaus cinema shorts” will invite you to the events of the second, third and fourth part of the “When Stories Meet” programme in Vilnius, Panevėžys, Marijampolė and Alytus. Upcoming programmes will include film screenings, meetings with people working in migration contexts, interviews with interesting, creative and inspiring people who have experienced migration first-hand. To find out about upcoming events, follow www.artscape.lt and www.lithuanianshorts.com for updates.

Aušra Raulušonytė

February 2, 2022